My rating: 5 of 5 stars

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

“The shade of your skin is not the whole content of you and your work. The shade of your skin should not be the measure of your worth.”-Salena Godden

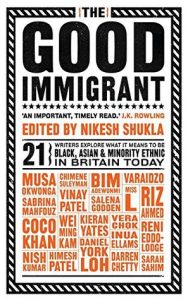

When you occupy a position of privilege the most important thing you must do in many situations is sit down and listen. For me The Good Immigrant was a ‘sit-down-and-listen’ book. It is a collection of 25 essays by black, Asian and ethnic minority communities in Britain – referred to there as ‘BAME’. The topics are varied but all address identity and race.

“So often positioned as invisible, neutral, and benign, whiteness taints every interaction we’ll ever engage in.”-Reni Eddo-Lodge

The essays range from academic to humorous in style, all drawing on personal experiences relating to being BAME in the UK. Many of the essays have similar themes and paint a cohesive picture, while almost as many are contradictory. Seeing the contradictions and the challenges of each individual was more powerful than a single cohesive narrative could have been. It demonstrates the complexity of people’s lived experiences and acknowledges that race is just one of the layers of identity each of the authors have.

“You are intermittently handed this Necklace of labels to hang around your neck, neither of your choosing nor making, both constricting and decorative”-Riz Ahmed

One thing to note is that this collection does not attempt to represent the whole immigrant or BAME experience in the UK. This is very clearly set out in the introduction, where it is explained that many of the writers know each other and all know editor Nikesh Shukla. Because of this there are many voices missing, and as almost all are successful people in the public sphere- journalists, tv presenters, actors etc.- there are layers of class privilege across some, though not all, of the essays.

This is an important collection, and a great starting point for readers to understand both the complexities of structural and institutional racism and the deeply personal manifestations of discrimination, especially those instances that occur within the specific context of 21st century Britain.

Two essays which have stayed with me, for different reasons:

Inua Ellams’s account of traveling to barber shops in Africa was fascinating. But the anecdote that stood out to me, and in many ways represents the struggle of so many of the authors in this book simply to be seen as human was this: ”Kenyan textbooks will tell you that a German missionary, Johann Krapf, discovered Mount Kenya. How is that possible when my ancestors have been grazing cattle there for centuries? There are 42 tribes in Kenya, you think not a single one of them looked up and thought ‘that’s a very big hill, let’s go check it out’.”

Reni Eddo-Lodge discusses the importation of American-centric media contributing to erasure of the black British experience, which is in many ways significantly different to that of America. She also sees this as ”a kind of displacement that when hand-in-hand with Britain’s collective forgetting of black contributions to British history”. In school the only black history she was taught was about the United States, she learnt about Rosa Parks but not the similar incident which occurred less than a decade later only 100 miles from the classroom she was learning history in. These examples represent a discomfort of many Britons with their past, and an attempt to consign racial issues in history to America alone.

Chimene Suleyman’s prose was raw and lyrical, straight from the heart. It immediately gripped me, and was a major influence in both purchasing and finishing this collection. Her words stand alone:

“We are simply the martyrs who were too afraid to die”

“Our ancestors were terrified. Do not forget that. Allow them the humanness of fear.”

“It is not antiques and money we are waiting to inherit from our families, but their skin.”

“We are heirs to their favourite chairs, and wedding rings, and the noose around their neck.”

What emotions did you have after reading? For some reason, I have a great sense of shame inside me ..

Perhaps because I am Australian I feel slightly distanced from the stories? Or perhaps it’s a measure of my privilege that is still unexamined? There was something deeply saddening about all these stories, and mostly I felt powerless, unable to influence except in the smallest of ways, the structures of power causing such harm.